Here is an essay on ‘Indian Agriculture’ for class 9, 10, 11 and 12. Find paragraphs, long and short essays on ‘Indian Agriculture’ especially written for school and college students.

Essay on Indian Agriculture

Essay # 1. Agricultural Development since Independence:

The principal programmes of agricultural development taken up during the Plans related the increase in agricultural production by bringing about land reforms thereby changing the social and economic structure of the rural society. Education was imparted to the rural folk in the new methods and techniques of better farming, horticulture, etc. through a comprehensive programme of community development and national extension.

Basic facilities like irrigation, transport and electricity were extended to the remotest parts of the countryside. Facilities for credit and marketing provision of price incentives and spread of literacy through adult education programmes were taken up to bring about a substantial rise in agricultural productivity.

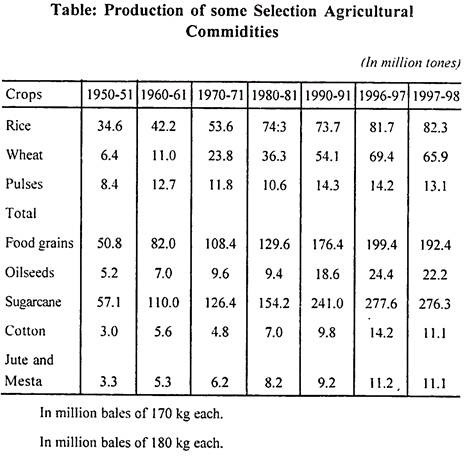

The outcome of these programmes for agricultural development during the Five Year Plans is given in Table:

Consequent to the heavy investment in the development of agriculture during the plans, output of both food and non-food crops has considerably increased, through much of the gain has accrued in the case of food grains production. From an extremely low output level of 51 million tones, food grains production increased to about 200 million tonnes in 1996-97. There was almost a ten-fold increase in wheat output and over two and a half times increase in rice production.

The productivity of food crops, particularly wheat, increased substantially after 1967-68 with the onset of Green Revolution. Coarse grains too showed some good trends, but growth- in output of pulses has been extremely tardy, increasing from around 8 million tonnes in 1950-51 to 14 million tonnes in 1997-98. Among the non-food crops, sugarcane output increased sharply from 57 million tonnes in 1950-51 to around 280 million tonnes in 1997-98. Cotton and jute production showed a four-fold and three-fold increase respectively. Oilseeds too recorded a four-fold increase in output.

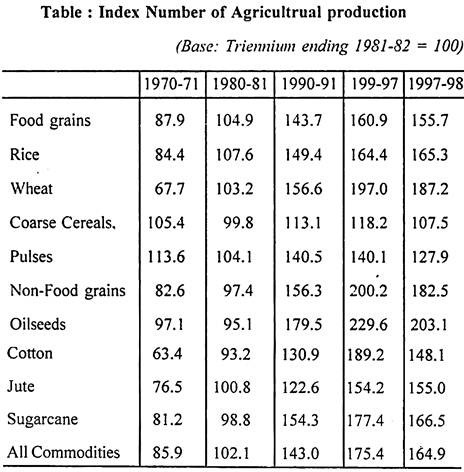

Thus, there has been a significant progress in agriculture, though the growth rate has not been very promising. A better idea of growth in agriculture can be made from the index number of agricultural production given in Table.

Between 1950-51 and 1963-64, the agricultural production increased substantially. However, in 1964-65 and 1965-66, because of a severe crop failure the agricultural production substantially declined. But, since then, there has been a marked increase the agricultural production.

The index of agricultural production for all commodities with triennium ending 1981-82 = 100), which stood at 85.9 in 1970-71 went up to 102.1 in 1980-81 and to 143.0 in 1990- 91 indicating rapid growth of agriculture in this decade. In 1996-97, the index number of agricultural production stood at 175.4 before it came down to 164.9 in 1997-98.

The major outcome of agricultural development during the Five-Year Plans has been that India, which frequently had to resort to heavy imports of food-grains, has now become self-sufficient in this field. However, this self-sufficiency is at rather a low level of per capita consumption. The per capita availability of food-grains has increased from about 395 grams per day in 1951 to only 484 grams per day in 1998, within food grains. The per capita availability of pulses has declined from 61 grams per day in 1951 to about 33.2 grams in 1998.

Much of the agricultural development has however been concentrated in only some regions like Punjab, Haryana, Western Uttar Pradesh, parts of Rajasthan and Tamil Nadu. The crops that have gained most from the planned development process is largely the food grain crops, mainly wheat and rice and sugarcane among the cash crops.

In the process the regional imbalance in agriculture growth rates has further widened and also the rich farmers in the well-to-do agricultural regions have cornered most of the gains of development. The rainfed (non-irrigated) areas have not shown very satisfactory progress during the Plans as is clear from the fact that pulses, which are essentially grown in rainfed areas, are shown an extremely low rate of growth.

It seems that most of the development efforts during the Plans have been concentrated on expansion of food grains so as to achieve self-sufficiency in food or to build up food security with much less concern for other crops.

Essay # 2. Cause of Slow Growth in Agriculture:

It may, however be pointed out that in spite of such a heavy investment in agriculture during our Five-Year Plans, the results in terms of output have not been highly satisfactory. There is scarcity of raw materials originating from agriculture. We are still dependent upon rainfall for irrigation of almost 70 per cent of our land.

In brief we have not made much of progress in the field of agriculture although we have put in so much of money in this sector. The reasons for this failure on the agricultural from may be easily found out in our faulty planning of agriculture.

The rate of growth in our agriculture has been very slow because of the following factors:

1. Less Emphasis on Quick Yielding Projects:

Unfortunately, in our planning much emphasis was placed upon those projects in agriculture which have a long gestation period. Quick yielding projects were not given their due importance, for example, much attention was paid to major irrigation projects while minor irrigation schemes were not given the place they deserved. Further, much attention was given to the increase in irrigation potential rather than looking after and maintaining the existing works. This has resulted in much loss of irrigation potential.

2. Inadequate Provision for Agricultural Inputs:

While the need to have good and sufficient inputs in agriculture is fully felt, there is still on inadequate supply of the same. Irrigation facilities, though expanding, are still not enough and vast tracts are still dependent upon rains. We are still victims of floods and droughts, pests and plant diseases. Obviously, not only should we arrange for much larger timely and sufficient supplies of the traditional inputs, but also develop locally available inputs.

3. Inadequate Credit Facilities:

The inadequacy of credit facilities has long been felt and regarded as one of the major drawbacks of our agriculture. For centuries, our farmers have been dependent upon non-institutional credit facilities with all the attendant limitations of the same.

The development credit, till recently, has been rather slow while the need of credit has been mounting realising that the programme of development of agriculture cannot be carried out successfully unless there is a provision for credit facilities, the authorities are now trying their best to promote credit facilities.

Cooperative credit is being boosted up; the Reserve Bank of India takes a special interest in development of co-operative credit, major commercial banks have been nationalised and are expanding their credit facilities to the rural areas. Regional Rural Banks have also been established and NABARD has been set up as an apex institution in the field of rural credit.

Essay # 3. Technological Change in Agriculture:

Indian agriculture, which remained stagnant during the pre- independence years and was further incapacitated by the partition of the country in 1947, made some reasonably good progress during the past four decades, especially since the onset of the Green Revolution in the late sixties.

The increase in production and productivity of major agricultural crops has indeed been commendable. Food grains production has expanded nearly four-fold since independence; wheat crop has witnessed revolutionary change in its production. General index of agricultural production has gone up from about 86 in 1970-71 (with the triennium ending (1981-82 = 100) to 175 in 1996-97 while that of wheat has gone up from 68 to 197 and that of rice from 84 to 165 over the same period. Non-food crops too recorded an over two-fold increase in production.

The country has thus achieved a fair measure of self-sufficiency in food grains and in quite a few other agricultural products.

The policy measures and programmes that have contributed to development of Indian agriculture can be categorised into two sets viz:

(i) Technological Changes and

(ii) Institutional and Organisational Changes.

Both of them have played a significant role in putting Indian agriculture on a sound footing.

(i) Technological Changes:

Measures such as development and application of high-yielding varieties of seeds (HYV seeds), introduction of multiple cropping through sowing of short maturity crops, use of fertilisers (NPK) on an extended scale, expansion in the area under irrigation, application of pesticides and insecticides, use of machinery and other modern agricultural practices in various operations, continued research and development leading to better varieties of seeds useful for dry land farming and rain-fed areas, etc. are among the major technological changes that have been made in agriculture.

Such changes have no doubt made tremendous contribution to rapid agricultural growth in India. In fact, it is universally accepted, that India would not have witnessed this tremendous upsurge in agricultural output, particularly in the output of food grains if these technological changes had not taken place.

(ii) Institutional and Organisational Changes:

The institutional changes mainly comprise changes in land tenure system viz., abolition of intermediaries, conferment of ownership on the tenants, security of tenure, land redistribution through ceiling on land holdings and consolidation of small scattered pieces of land into larger farming fields. Through such institutional changes the whole organisational structure of Indian agriculture has undergone a change.

There are also changes in the spheres of agricultural credit where many institutional sources of finance such as cooperative societies and regional rural banks have expanded their network and financial activities to meet credit requirements of the fanners on easy and soft conditions thereby releasing him from the clutches of the greedy and exploitative moneylenders. Setting of regulated markets and promotion of cooperative marketing societies are also a part of organisational changes.

The institutional and organizational changes have also played their part in agricultural development. The abolition of zamindari system and the conferment of ownership rights on the tenants brought in the necessary incentives and will to do hard work on the farms which now belonged to the cultivators and not the ruthless zamindars.

This directly contributed to growth of agricultural production. Land ceilings and land redistribution in the favour of landless also contributed similarly to agricultural growth. Prevention of exploitation of tenants through excessive rents charged by the landowners, giving them security of tenure by preventing their ejectment at will, did create the necessary climate for hard work and farm improvements by the tenant cultivators. Consolidation of land holdings allowed for better land management and use of improved techniques.

But it is believed that the role of institutional and organisational changes in agriculture played only a limited role in its growth. This is because, firstly, these institutional reforms, particularly the land reforms, have not been implemented fully in letter and spirit; they largely remain on paper.

Their tardy implementation due to opposition of powerful political pressure groups and vested interests did not release much growth generating forces. Secondly, in the absence of technological breakthrough in agricultural operations, the institutional reforms could not contribute much to the growth of agriculture.

Thus, whereas there was a high growth in agriculture during the first Plan, it tapered off during the Second Plan. The Third Plan saw the worst agricultural crisis in the country; the actual output of many agricultural goods such as food grains, oil seeds and raw cotton at the end of the Third plan was even lower than the output level at the end of the Second Plan.

Meanwhile, efforts were made to bring about a technological breakthrough in agriculture. New high-yielding varieties of seeds were discovered and used with substantial doses of fertilizers in irrigated areas. Mechanisation was also introduced and use of tractors, harvesters and other mechanised farm equipment was encouraged. The results were really revolutionary.

There was manifold rise in agricultural productivity and output of food grains expanded sharply. Ever since the new technology was introduced in the late 1960’s, there has been no looking back. Over the past years the country witnessed some periods of worst droughts, yet our agriculture has come out unscathed, fluctuations in yearly production have been minimised and beneath these fluctuations one could see the underlying increasing trend rate of production.

Technological changes have thus been largely responsible for our tremendous agricultural progress and upsurge in food production. Till the new technology was introduced, agricultural progress was extremely slow and uneven in spite of the major Institutional and organisational changes in this field.

But could technological changes alone bring about such revolutionary changes in agricultural scenario. The answer is no. How the new technology could be applied to small scattered and fragmented tiny pieces of land holdings. In what way could irrigation be developed on pieces of land that did not form a single farm.

Thus, consolidation of landholdings, an important organisational change, helped application of new technology. Again in the absence of tenurial reforms-abolition of zamindari and conferment of land ownership to the tenants, there were not many possibilities of adopting new technology.

This is because the zamindars or the absentee landlords living in the luxury of city life could not have any inclination to spend on new production methods whereas the poor tenant cultivators had neither the means nor the incentive to buy modern technology. Again in the absence of organisational reforms in the field of agricultural finance, the poor formers could not get access to credit that has enabled him to go in for modern production methods.

Thus, whereas technological change has made available modern production methods, institutional and organisational changes have provided an appropriate climate for their adoption and application. Without technological change, surely there could not be much development in agriculture; and hence it is a necessary condition of agricultural growth. But this technology may have remained largely unused if the necessary incentives and facilities for its use had not been provided by institutional changes.

Thus, both the technological as well as the institutional reforms have played their role in agricultural development of India. But, whereas the role of institutional changes has been a little bit controversial to that of technology has been universally accepted. But no one can deny the role of institutional reforms in facilitating the adoption and application of modern agricultural technology; it would have remained largely ineffective or extremely limited without organisational and institutional changes.

Essay # 4. Measures to Raise Productivity:

Agrarian reforms are often considered equivalent to land reforms. Basically this is not so, unless land reforms are considered to include everything that should be done to improve agriculture in every sense. Basically, agrarian reforms would include the reforms connected with the land tenure system; and also include all other steps designed to improve agricultural productivity.

I. Intensive Cultivation of Land:

Agriculture forms the backbone of our economy and a major portion of our working population is engaged in agriculture. Also another sizeable portion of population is dependent upon agriculture for its living in an indirect way. These factors are leading to a high degree of pressure upon land, a pressure which should be reduced if possible. Land is a factor which cannot be increased substantially.

Therefore, the only long- term solution regarding the augmenting of land supply is to increase the intensification of its cultivation and increase in productivity. Each piece of land must be made to yield more than one crop and each crop yield must be more per hectare, so that in effect the supply of land is more even with the same geographical area.

II. Reducing Population Pressure:

Reducing the pressure on land is connected with its productivity also. As it is, there is a large- scale disguised unemployment of labour in land. With an easing of pressure of population on land this disguise unemployment can also be reduced. As we know, disguised unemployment implies that the labour employed at the margin has a zero or negative marginal productivity so that a withdrawal of labour would lead to either an increase or no change in total output.

III. Consolidation of Land Holdings and Implementation of Land Ceilings:

Productivity is very closely linked with size of the operational holdings. As it is, our agriculture is riddled with two extreme types of holdings. Some of them are very large and some of them are too small and fragmented.

It is necessary that the operational holdings should more or less be such as would yield maximum yield per hectare. Currently, our agricultural productivity is very low. Very large farms are inefficient, partly due to the fact that there is a good deal of wastage in them. Similarly, very small farms are also inefficient because the small farmer cannot afford to use the necessary inputs.

Accordingly, agricultural policy has to include a firm approach leading to the development of economic holdings which should be operationally most efficient. To this end, it has been thought fit to make sure that there are no holdings of too big areas; and that at the same time, very small holdings are consolidated. Hence, land ceiling laws have been passed and are being pursued vigorously. Similarly, the policy of consolidation of holdings is being implemented more effectively.

The surplus land released through the implementation of ceiling laws is being distributed amongst landless labourers. But though this step will bring a sense of satisfaction to the poor agricultural labourers, it can retard agricultural productivity since these new owners will have very small holdings which may not be operationally very efficient.

Another aspect of improving land productivity concerns the provision of requisite inputs. Agricultural productivity is a matter of proper inputs and their use. In India, the supply of a number of important inputs is in short supply.

We have still large areas which are dependent upon rain. It is desirable to have, instead, assured irrigation either through canal water, tank water, tube-wells or some other source. Currently, we are using only a small portion of our available water resources for irrigation purposes. More land should be brought under HYV seeds.

Use of chemical fertilizers and pesticides must be further encouraged. Also, a proper agricultural policy has to make sure that the farmers’ problems of credit and marketing are solved to their satisfaction so that they are assured of reaping the fruits of their efforts.

IV. Reforms in System of Land Tenure:

Another very important aspect of agricultural productivity which has received attention of the government right from the beginning is the land tenure system. It is believed that ownership and the assurance that the fruits of one’s labour would be available to oneself, go a long way in ensuring hard work and productivity. It is this and also the sense of social and economic justice that prompted the authorities to take steps to abolish zamindari system in the country.

With the existence of zamindari, the tenants were subject to all kinds of exploitation by the landlords and could be evicted from their lands at the will of the landlord. This created a great sense of insecurity in the tenants and they never felt interested in improving the productivity of land through investment, nor were they in a position to raise funds for such investment.

The landlords, on their part, were basically interested in getting as much as possible out of the land and so they also never thought of investing in land. Thus, land reforms or reforms in the land tenure system were implemented. Landlordism was abolished and the tenants could purchase land from the government which took the possession of land on payment of compensation to the landlords. The implementation of these reforms had, however, been faulty.

V. Other Measures:

The last plank of reforms to increase agricultural productivity would be concerned with social and economic justice. There is no reason why the fruits of agricultural workers and farmers should not be available to them. To this end, therefore absentee landlordism and intermediaries must be rooted out from wherever they still exist in Indian agriculture. Also the farmers must be freed from the clutches of money-lenders who exploit them in more than one ways.

The custom of bonded labour has been abolished. The farmers should be assured of sufficient, timely and cheap credit for their farming activities. Various steps have been taken to this effect and it is hoped that very soon the rural scene would be transformed beyond recognition.

In, the same way, implementing the provision regarding minimum wages to the agricultural workers, increasing the employment opportunities and reforming the agricultural marketing would go a long way in providing social and economic justice to the farmers and agricultural workers.

If along with these reforms, subsidiary occupations like bee-keeping, dairy farming, poultry-farming and the like are developed, it would improve the economic conditions of the rural masses enable them to spare resources for investment, ease the pressure on land and act as a great deterrent against any kind of exploitation and thus keep in tremendously improving productivity in agriculture.